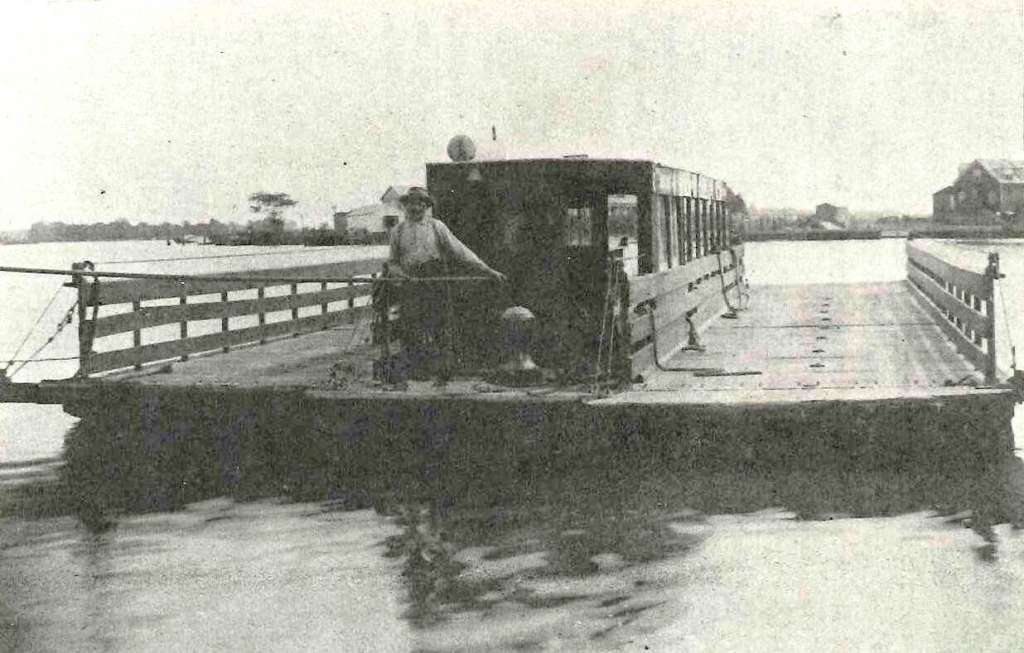

The first ferry to operate in Texas waters, the Lynchburg Ferry, ranks among the oldest continually running, free-of-charge ferries in the Nation, being founded in 1822 (1997: Hon. Ken Bentsen, Remarks, House of Representatives). Harris County has operated the Lynchburg Ferry since 1888 with no charge to the public for passage, being the only county-operated ferry in Texas. In 1920, the first diesel-powered, cable-free ferry boat, the Chester H. Bryan, was put in service at Lynchburg by Harris County. In 1945, Lynchburg became the first two-ferry system in Texas with the addition of the Tex Dreyfus (see Photographs in Appendix of early ferryboats). The William P. Hobby and the Ross S. Sterling that are in operation as of 2011 replaced the older ferryboats in 1964 (2004: Wilbur Smith page 5-1).

The Lynchburg Ferry crosses the Houston Ship Channel just downstream of the confluence of the San Jacinto River from the north with Buffalo Bayou from the west. The two continue southeastward to fall into Galveston Bay. Highway 134 or Battleground Road connects State Highway 225 on the south to Interstate 10 on the north via the Crosby Lynchburg Road.

Named for founder Nathaniel Lynch, the passage across the San Jacinto River near the confluence with Buffalo Bayou had been officially licensed with ferry rates in 1829 by the ayuntamiento at San Felipe (GLO: Minutes of the Ayuntamiento San Felipe, 1829). One of four in 1837 Harris County, Lynch’s Ferry, recognized by Commissioner’s Court on April 18, 1837, was allowed six and one-fourth cents per person or live animal and 25 cents a wheel for light carriages or wagons. Loaded vehicles paid 37 ½ cents per wheel.

Unlike Lynch’s day operation, 6 a.m. to 10 p.m., until recently, Harris County operated the ferries 24 hours, seven days a week except in inclement weather. Lynch moved passengers via a single boat, whereas Harris County presently utilizes full power, non-cable ferries, each carrying 12 vehicles or 110 tons. The average time to cross is under three minutes, loading taking five minutes and unloading taking about one minute. During peak times, a two-boat wait is typical with Houston Ship Channel traffic having the right-of-way.

Operated by the Lynch family until 1848, the Lynchburg Ferry provided critical passage across the confluence of the San Jacinto River and Buffalo Bayou. Sold to various operators between 1848 and 1888, Harris County acquired the Ferry and Landings in 1888 through article 2351, V.T.C.S. Article 2351 which stated that “Each commissioners court shall: …..2. Establish public ferries whenever the public interest may require.” Although private ferry tolls were authorized by Texas State Statute (articles 6801 and 1476, V.T.C.S.), public operations have not been allowed tolls (1977: Attorney General of Texas Opinion No. H-990). Harris County had charged tolls for only two years being ten cents for foot passengers, fifty cents for one-horse vehicles, one dollar to two-horse conveyances, $1.25 for four horse vehicles until August 14, 1890.

In 1930, the two-boat system ferried about 145,000 cars per year, while in 2004 the boats ferried, on the average, over 800,000 cars or 2200 vehicles per day (2004, Wilbur Smith Report: pg 1-2). Historically, as today, the ferries served Harris County residents that live and work at the Port of Houston and petrochemical plants on both sides of the Ship Channel. The construction of the Fred Harman Bridge six miles downstream on Highway 146 to Baytown has relieved some of the ferry load, particularly in inclement weather. Five miles upstream, the Beltway 8 Bridge over the Ship Channel lessens some of the ferry congestion. The Hartman is a free bridge with the Beltway 8 operating as a toll road. However, the detour on the bridges, instead of the more direct ferry, adds five to eight miles or more to a commute.

In the early 1970s, enterprising carpooling workers found a way to cross the ferry on foot, saving the long wait in the line of cars during rush hour. The group purchased an older second automobile, located a parking space on the San Jacinto side of the crossing, and parked their car each morning on the north side of the ferry to avoid the long lines of vehicles going to work in the petrochemical industry (2005: personal communication to J. K. Wagner).

Harris County constructed a new main ferry office on the Lynchburg side in 1982 and purchased the Garrett Morris ferryboat in 1988. Both the north and south landing ramps were rebuilt in 2003, the ferryboats were repainted, and a new road opened to the north landing. In 1988, part of the movie, Full Moon Over Blue Water, starring Gene Hackman and Teri Garr was filmed at Lynchburg.

Nathaniel Lynch, born in New York, came to Texas from St Charles County, Territory of Missouri 36 years old with wife, Frances, nee Hubert, and three children. Having Ferry experience at Portage Des Sioux around 1818, Lynch laid claim to the league of land (4428 acres) where an old Spanish Coast Road crossed the San Jacinto River. In 1828, Stephen F. Austin showed part of the road crossing at Lynchburg as an offshoot of the Camino de Opelus (GLO: ca: 1828, Austin Sketch Map).

Nathaniel Lynch, born in New York, came to Texas from St Charles County, Territory of Missouri 36 years old with wife, Frances, nee Hubert, and three children. Having Ferry experience at Portage Des Sioux around 1818, Lynch laid claim to the league of land (4428 acres) where an old Spanish Coast Road crossed the San Jacinto River. In 1828, Stephen F. Austin showed part of the road crossing at Lynchburg as an offshoot of the Camino de Opelus (GLO: ca: 1828, Austin Sketch Map).

The old Spanish Road, also known as the “Lower Orcoquisac Road,” ran on a natural ridgeline south of Brays Bayou toward a crossing of the Brazos near Hodges Bend to hug the coastline of Texas. According to Martinez in 1690, the lower road was not a desirable route in summer due to the lack of available water (Center for American History: Archives of San Francisco de la Grande). Early in the 19th century, trappers lived along the Lower Road to round up herds of Spanish horses on the Brays prairie, driving them to sell in Opelousas, Louisiana (General Land Office: P.W. Rose, English Field Notes).

After Anglo Americans settled along the Brazos River, Oyster Creek and Buffalo Bayou, as well as Clear Lake, in the 1820s, the road leading to Lynch’s Ferry became popular. The route was also known to have few Indians (1986: Henson: Paper to Texas State Historical Assn Meeting: “Who was Crossing the Lynchburg Ferry: The Runaway Scrape, 1836” page 1).

In the panic that preceded the Battle of San Jacinto, April 21, 1836, the Lynchburg Ferry saved the lives of an estimated 5,000 fleeing residents between March 17 and April 20. Many of the families, carrying horses, cattle and carts had to camp on the west approach for three days in order to pass (Henson, ibid, p. 8). When the Mexican Army approached the Ferry, Mrs. Lynch and her family took the boats downstream, keeping the invaders from crossing the River. Following the victory by General Sam Houston at San Jacinto, the returning residents of the Brazos River and places westward, obstructed normal travel at the Lynchburg Ferry on Easter weekend, as well as the following two weeks. Many returned home to find only ashes (Henson: pg 14).

Nathaniel Lynch had commenced a ferry service in 1822 from his first home on Crystal Bay, running across the San Jacinto River to a landing south of Margaret McCormick’s house on Peggy Lake (GLO: Lynch English Field Notes by J. Iiams). The Crystal Bay house was sold to Clarissa Patching for $750 (15 Sept. 1843). The ferry was described as “a raft that carried only one buggy or wagon at a time because of the danger of spooked horses” (Houston Post: 1976; Clopper’s Journal, 1828). Lynchburg Ferry After receiving a license and toll rates from the authorities at San Felipe de Austin, Lynch was requested in 1829 to move his ferry service upstream to the peninsula formed by a meander of the San Jacinto. The license was apparently issued for that location, but Lynch did not remove his operations immediately, causing many irate travelers to complain to the government at San Felipe. The 1830 Ferry License carried the stipulation that the ferry be operated “at the crossing of San Jacinto at the mouth of Buffalo Bayou for one year beginning January 1, 1830” (Minutes, Opt cit: 1829, 1830).

Lynch moved to the area just downstream of the present landing in 1830, constructing a landing and house at that location to fulfill his Ferry License requirements (Austin County Deed Records: M/68). By 1834, the town of Lynchburg was platted and Lynch moved to the present ferry location, opposite the new town of San Jacinto on the south bank (see Map: Town of Lynchburg 1820 – 1950 in Appendix; Harris County Deed Records P/59; L/576). Lynch also platted the town of San Jacinto on the south bank of the River. Nathaniel Lynch died on February 14, 1837 and rests in the Lynchburg Cemetery.

Lynch moved to the area just downstream of the present landing in 1830, constructing a landing and house at that location to fulfill his Ferry License requirements (Austin County Deed Records: M/68). By 1834, the town of Lynchburg was platted and Lynch moved to the present ferry location, opposite the new town of San Jacinto on the south bank (see Map: Town of Lynchburg 1820 – 1950 in Appendix; Harris County Deed Records P/59; L/576). Lynch also platted the town of San Jacinto on the south bank of the River. Nathaniel Lynch died on February 14, 1837 and rests in the Lynchburg Cemetery.

The Lynchburg Ferries played a role in the Civil War when the Confederate Army converted the local sawmill to a munitions factory, producing “ball and cap” guns out of flintlock weapons. After the Civil War ended, the town of Lynchburg thrived with new stores, a Mill, saloons, hotels and houses. Following the 1874 fire in the lower part of the town, the owners immediately rebuilt. Plans were made by the A. P. Tompkins to develop a shipyard and turning basing in the cove directly east of the town.

However between September 17 and 21, 1875 a disastrous hurricane hit the Texas coast, killing eleven at Lynchburg, scattered the ships and barges of the Direct Navigation Company, and sinking the tug Superior in Old River. Many houses, including the Old Ferry House, warehouses and the Tompkins Hotel were a total loss. One of the survivors clung to a house roof that floated him to safety. The survivor related that the storm surge up the river was about 30 feet high. Not a home stood on the Bay shores (Daily Houston Telegraph, 21 Sept 1875, 4, c.3). Undaunted, the residents built again, the Tompkins family believing the worst was over with brother, R. V. Tompkins running the family hotel and warehouse business. However, four years later, April 1879, the Tompkins improvements and businesses were again destroyed by an unusual storm.

Ferry rates for the Lynchburg ferry traditionally set by Harris County Commissioner’s Court beginning in April 1837 (Harris County Commissioners Court [HCCC] Minutes, April 18, 1837, A/3). F. C. Sandow received the Lynchburg Ferry franchise in February 1884 with the following set rates: foot passengers paid 10 cents each; a one horse vehicle paid 50 cents; a two horse vehicle $1.00; a four horse vehicle $2.25; a man and horse cost 25 cents; cattle, horses, mules, jacks or jennies under five in number paid 10 cents each; over five in number paid 7 and ½ cents each; with hogs, sheep and goats at 2 cents each (HCCC Minutes, February 14, 1884, E/59).

By the time Harris County took over the ferry in 1888, the population of Lynchburg had declined to 178 persons. On September 4, 1888, Harris County established a free ferry service at the Lynchburg crossing (HCCC Minutes, E/546). Harris County then added a public ferry to Zavala Point to the west in 1900 that continued in service until 1931. The last Zavala Point ferryboat had motorized paddles mounted on the side (The Highlands Star, 9 Sept 1976, 55, Muril Hart “Lynchburg”).

When the 1900 storm hit Galveston, Lynchburg also had the town buildings wiped out. R. V. Tompkins rode a timber up Old River. R. V. Tompkins then left Lynchburg and his plans for a turning basin to sons, Frank and Thomas, who continued part of the business, helped by the 1904 dredging of the Houston Ship Channel. Lynchburg became a station for the dredges along with Harrisburg and Morgan’s Point. The new business created stores, a hotel, warehouse, icehouse and visiting tourists sightseeing on the Mary Evelyn (Houston Chronicle: 1935, Tompkins, “Reminiscences”).

The last straw came with the August 1915 hurricane that destroyed all the Lynchburg structures, severely damaging the ferry landing and ferries. The Tompkins family pulled out of Lynchburg forever. The population of Lynchburg dropped below 75 persons. The Harris County ferries continued in operation, providing access to industry and homes on both sides of the channel.

Business began to slowly return to Lynchburg in the 1950 with the founding of a new shipyard providing barge and boat cleaning services, later marine service companies, and more recently the Coastal Water Authority, the largest present industry in the old town. The Harris County ferries contribute economically to the region, maintaining Lynchburg as a focus of industry and commerce on the Houston Ship Channel with thousands passing through the old town every year. As of 2011, Harris County continues a free ferry service using two boats, the Ross S. Sterling and the William P. Hobby.

Janet K. Wagner

March 10, 2011